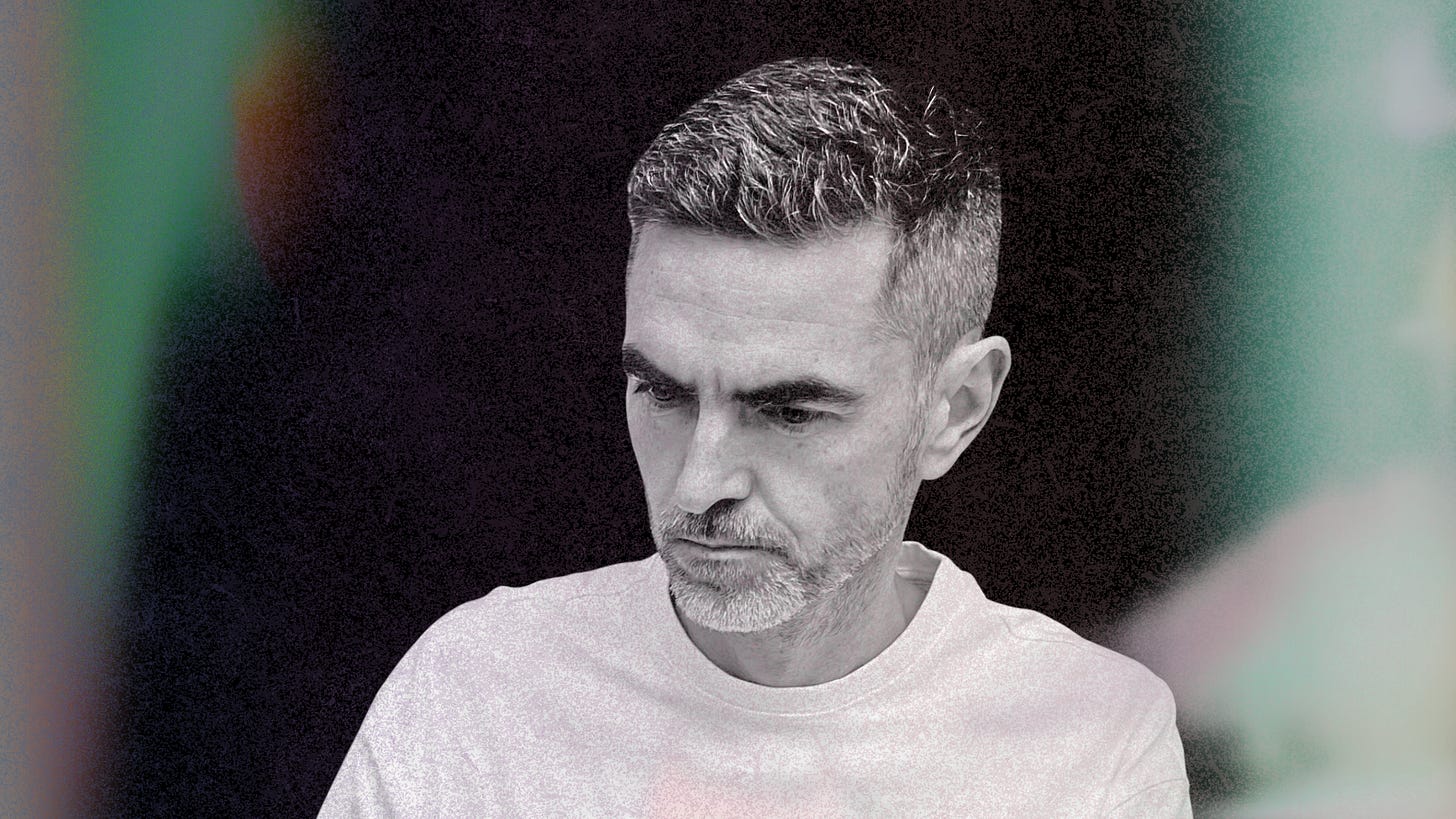

My perplexing two-week conversation with Bogdan Raczynski

One of IDM's most playful artists delights in dodging, contradicting, and keeping me guessing.

What’s the point of the artist interview?

To snatch a small glimpse of their creative mind, perhaps an insightful quote which decodes how they produce the art loved by so many.

As a journalist by trade, that’s what I’m forever seeking. Hunting for a little kernel of poetic meaning, something memorable which I hope lingers with readers after they finish the piece.

But what happens if the artist in question has other ideas?

Bogdan Raczynski has long been a creative forced in electronic music. A stalwart of the braindance/IDM scene, the Polish-American musician emerged seemingly out of nowhere in the late 90s, releasing a flurry of records on Richard D James’ Rephlex label.

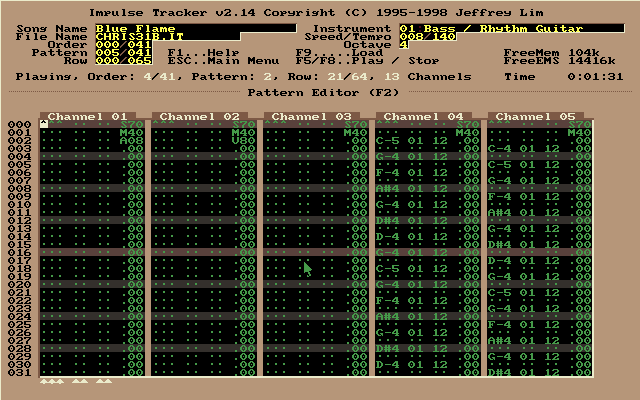

At a time when electronic music was becoming increasingly chaotic and complex, Bogdan’s work was right at the forefront. His mangled and squelchy songs were constructed on rudimentary tracker software – programs which, to the uninitiated, look more like ancient RPG interfaces than tools for making music.

James had nothing but praise for his work, saying during an interview with Resident Advisor in 2019: “Bogdan was a massive inspiration for some of my tracks on the Drukqs album… the fact he was doing it all on a shit PC tracker… totally amazing. This was before 99.9 percent of people used the computer for everything. His records are so underrated.”

Quite the endorsement from the figurehead of IDM.

1999 was a huge year for Bogdan, releasing two records on James’ Rephlex Records label: Boku Mo Wakaran and Samurai Math Beats. What leaps out from these albums is the contradiction coursing through them. There’s almost a sunny disposition threading through the sweet melodies and and plinking soundscapes, offering a warmth often absent in the metallic thrum of breakbeats and acid techno.

But they also flip the switch to defiance and unease, often without warning.

Then, in 2001, Bogdan released myloveilove, an album that – stealing from my own words – captures the intimacy of companionship with the kind of tenderness not usually found in the genre.

What follows is two decades of mad-scientist electronic experimentation, cementing Bogdan as an essential figure in this corner of the music world.

This year he put out Slow Down Stupid, perhaps his most perplexing work yet. On the surface it’s a mangled interpretation of last year’s You’re Only Young Once But You Can Be Stupid Forever, the record ending with an achingly-slow, 52-minute ambient cut. It drifts along in a subtly-menacing fashion, closing out a record of undeniable eccentricity.

It was off the back of this release that I approached Bogdan for an interview. The accompanying press release alone – coupled with his increasingly apoplectic Instagram posts – suggested there was a rich seam to tap: “Displaced commentary for displaced times. Deconstructed. Decnstrcccttttt. Dstrctn. Distractions, one-sided abstraxxxtions.”

He agreed, but only to an email exchange. Not my preferred method, but I was glad to speak with the man through any medium he’d allow.

His willingness to oblige in an interview in the conventional sense was something I foolishly misinterpreted.

The first question on my mind was who Bogdan was calling ‘stupid’? I fired off the question and waited for his reply.

“I do not know”, he typed in an email I received a day later. “It was more of a feeling than a thought. Sometimes I am tired of thinking. Sometimes, I do not trust my thinking. Sometimes I trust my feelings more. What do you feel about it?”

It’s not often that your first question gets immediately flipped by the interviewee. Having a good stab at it, I told him that the title appears to have a playful sting to it – maybe it’s teasing but also compassionate, like telling his listeners or the world to take a breath. I also wondered if there was an element of the political in there.

The ‘smart in charge’, our politicians and leaders who seem to be marching the world into a darker place every day. Maybe it’s better to be ‘stupid’ in that context?

Five days went by with no response.

I’ve screwed it up, I thought. My reply was a test, and on the basis of what I think his album title means, he’s terminated the interview.

Then, one Thursday afternoon, he emailed: “Yes, you understand the message. I would also add that we are all stupid – for our complicity, for our participation. For not doing enough. For not digging ourselves out. For effectively making our own lives worse.”

I wondered if this would be a facet of our conversation. Following Bogdan’s Instagram Stories these days is more akin to a newswire service focused on the atrocities happening in Palestine. It’s something he’s clearly passionate about, using his voice to amplify what has unfolded in the Middle East over the past two years.

I asked him directly if the “complicity” he’s referring to is about Gaza. He replied: “Yes, I am thinking about Gaza, the Congo, Sudan, and the Uyghurs.

“Also lately, Germany’s other genocides in Namibia, and the complicity and inability of our supposedly civilised governments that have yet to truly atone or pay real reparations, not just promises of investments and projects.

“And, by association – and also by our direct participation in capitalism – all of us are complicit.”

This was a place I imagined the conversation might go, but perhaps not so quickly. Pushing him on this idea of complicity, I wanted to know what forms of resistance he believed were useful. At the time we were exchanging emails (August of this year), artists had begun removing their music from Spotify in protest of CEO Daniel Ek’s investments in weapons tech.

~During our conversation, Bogdan’s work was still available on the platform. As of November 2025, he has removed almost all of it~

He fired off a quick and frantic reply: “I have this conversation occasionally from time to time. My impulse is to be extreme and insist on cutting ties. But the question then is why am I doing it: is it to signal my virtue to others?

“Is it to quell my own guilt? What about Google’s even bigger and more directly connected investments in the IDF? Am I also going to remove everything of mine from Youtube, also owned by Google?”

His message continued: “In that sense, boycotting becomes not just a weapon against capitalism but also a means for attempting to blunt one’s own guilt. But in the case of the latter, it has the potential to make things worse – if you say to yourself, “OK, I have boycotted Spotify and I feel better now”, but you continue to support Google, then you have only made the problem worse.”

I was starting to get the sense of a person utterly exasperated by the world they inhabit: enraged by the injustice and also knowing they are unable to do anything about it. He suggested we should all do what we can afford to do, but isn’t optimistic about what that achieves. His message ended by saying: “We are well beyond the point where we need to start self-correcting.”

This pessimistic outlook feels at odds with the playfulness of his music. Ever since 1999, there’s been a sense of childlike innocence to much of what he produces, and the DNA of that notion is still present in parts of Slow Down Stupid.

Doing my level best to drag the conversation back to his latest record, I wondered if the title was telling its listeners to disconnect and do what they can, where they can.

He responded: “I really do not know the answer, and I am not trying to be direct with the album title. It just popped into my head without any thought in the same way that creative ideas sometimes just pop into my head. And when that happens, I do my best to let it be.”

But I thought I “understood the message”? Was Bogdan toying with me? The answer came during a flurry of messages the next evening.

Asking him how Slow Down Stupid is connected to 2024’s You’re Only Young Once But You Can Be Stupid Forever, he simply replied “ear of the beholden”. Not satisfied with the bluntness of the reply (during an interview about music, no less) I challenged him: he doesn’t seem to want to talk about the themes of the music, does that feeling extend to the music itself, too?

His response: “Talking about music is like reading your marriage vows from a 500-page legal agreement.”

OK, tough one to swallow for a music journalist.

Perhaps he would like to talk about music that he’s been listening to instead? More fool me for thinking that particular question would fly.

Before I’d even sipped my coffee the next morning, I read his reply: “Sound to me is supremely distracting in this way that I cannot do anything else when it is organised and rises above the din. So it is just easier to sit in silence and I rarely have anything on because I am rarely not doing something.

“That sounds like such an artist thing to say and I say it unapologetically, but honestly it is sometimes a fucking pain in the ass because silence is not always pleasant. I long for companionship when I am doing some drudgery kind of work like laundry or dishes or whatnot.

“Wow, I think in the process of writing, I’ve just discovered that that is what sound is to me. A friend. When a friend comes to your door you let them in, you have no choice. Why would you not want to do anything but let them in? What could possibly be more important or better than letting them in.”

Head to Bogdan’s site and you’ll now see ‘sound my friend’ as an official future release. I shall be taking some small credit for this, if it ever materialises.

He explained that the Slow Down Stupid title also came to him during a conversation with an interviewer, but – and I sensed a hint of glee – “I do not think I will be hearing back from them ever again.”

And there it was.

This wasn’t an interview. It was a game of chess – and the ‘checkmate’ would be frustrating the other into ending it.

Intrigued, I asked what happened to cause such consternation in his former interviewer: “Nothing in particular happened, I just have a habit of going off on my own and rambling on and not really paying attention to the assignment.

“I think that most people are not really comfortable being challenged when artists challenge these kinds of structures. Maybe they think that music and therefore musicians should behave in a certain way. Although I am willing to play along, I think the whole thing is a charade.”

His tirade continued: “I used to have this feeling that all music was valid and meaningful – from the noise to the pop. Now, I feel like it is all hands on deck, and if you are not angry and thinking about ways to subconsciously or surreptitiously or subliminally hide messages or be super direct about engaging with the life and death issues we are all complicit in, then get the fuck out of the way and stay in your basement because you are actively holding humanity back.”

This came as a surprise. Trying to get it straight in my head, I attempted to map Bogdan’s reasoning: he’s passionate about wanting art and music to make people engage with life and death issues we’re all complicit in. In the same breath, he refuses to clarify the message or underlying theme of his own work.

I called out the contradiction. Minutes later, I received this final reply, which I’ve produced below in its entirety.

“I appreciate you pushing me on this.

short:

i do not know and that is ok

long:

- there are quite literally people whose job it is to know how to deal with life and death issues

- there are quite literally people whose job it is to govern and lead us in a way that is good for people

- the above two should be impossibly interwoven for time immemorial at the exclusion of every other governing model especially religion

- we are so desperate for a resolution from the worst of humanity that rather than make better voting choices we look to the stars

- literally we idolise movie stars and musicians and celebrities and loud weirdos because they are loud and we associate loud with honesty

- only for us to find out that the majority of these people are either far right or racist or transphobic or ok with babies dying or shooting two missiles at a digital camera

And finally

- we

- meaning white men because that is what i am

- have forgotten how to say

- i do not know

- it is ok to say

- i do not know

- shut your mouth

- think

- reach the conclusion that actually

- i do not know

- i have ideas

- but everyone has ideas

- but ultimately i do not really know

- a great thing happens when you say i do not know

- suddenly you have turned it into a conversation

- suddenly you are multiple people trying to figure out a problem

- suddenly you rely on a system to try and figure out a solution

- this is called

- science

- if you do not have ideas chances are that a scientist does

- maybe there is a book on it

- do not just fucking guess

- shut up and say

- i do not know

PS

- i am an artist

- this is not a dirty word

- it does not mean i am better

- it means i have different eyes

- we all have different eyes

- i personally think that every human is an artist

- but that is a different conversation

- i feel that the joy and gift of art

- is the ability to express what you see

- literally or figuratively

- within yourself within the world

- if there is even a difference

- it does not mean you have answers for what you find

- it simply means that you are allowing this creative part of yourself

- to have space.”

With that, we exchanged a couple of niceties and the interview was over.

Looking back, I’m not entirely sure whether I interviewed Bogdan or whether Bogdan interviewed me. Or possibly neither of us interviewed anyone.

What I do know is that I left the exchange feeling slightly dazed and a little provoked – but also weirdly energised. If his goal was to frustrate the assignment, I think he failed. But if it was to make me think harder about complicity, art, silence, and stupidity? Perhaps he succeeded.

For an artist who insists he has no answers, he certainly leaves you with a lot to think about.

All of Bogan Raczynski’s music is available on Bandcamp.

Fascinating piece Oliver. I was not familiar with his work. A bit of cat and mouse there, with the dynamics between interview-er and ee laid bare. One thing he said has been much on my mind lately, what with our dangerously fucked up environment (in my case, the US): "I would also add that we are all stupid – for our complicity, for our participation. For not doing enough." Been hitting home more than ever, as I'm in the middle of reading about 1930s/40s Nazi Germany (a book called "Europe Central"). Yet, listening to Slow Down Stupid, there's a good amount of whimsy and humor here, i.e., "meant for our imagination". Brings to mind the Residents. Can't go wrong there!